Watching your weather app for possible snowstorms? Apologies to my sun-loving family members. I still love a good snowfall. I’m retired and don’t need to go anywhere. I can watch the white stuff outside my windows as it blankets the world in sparkling beauty, covering the brown bleakness of winter. On an unofficial snow day—which is not quite the same as a teacher snow day—I’m tempted to feast on hot chocolate and heavily buttered toast, curl up on the sofa wrapped in a warm blanket, and read a book or two.

Watching the snow barely cover the roads by my house, I’m reminded of snowstorms from years past. I remember one not that many years ago (January 1996)—okay, my kids were teenagers, so maybe it was long ago—the snow was deep enough to build tunnels from the house to the garage and crawl through on our bellies.

I remember building full-sized snow forts on the baseball field during elementary school recess and pelting outsiders with hard-packed snowballs.

My parents told of walking to school while the snow piled up to the telephone wires.

But not everyone feels the same delight when the white stuff falls. If you dread winter’s greatest blessings, here are a few tales from America’s history to remind you that it could be worse!

The Storm of the Century

March 12-15, 1993, was dubbed “The Storm of the Century.” On Thursday, March 11, the system formed over Mexico and brought high winds and hail to Texas. It then moved along the Louisiana coast before slamming into Florida on the morning of March 13, producing tornadoes, high waves, and lightning.

Thundersnow occurred when warm tropical air rose rapidly, creating unstable conditions in the upper atmosphere and producing snow, with 60,000 lightning strikes from Georgia to PA. Forecasters called the conditions feeding this storm a “meteorological bomb.”

Over the following days, the Coast Guard rescued 235 people at sea. A 200-foot freighter sank, and another ran aground on a coral reef. Some seafarers faced 65-foot waves. Many people died or were lost at sea.

As the storm moved up the coastline on Sunday, March 14, it intensified into a blizzard. It reached as far west as the Dakotas, bringing more than $5 billion in damage, power outages, 144 mph winds in New Hampshire, a foot of snow in Florida and Alabama, and 56 inches of snow on Tennessee’s Mt. Leconte.

By Monday, March 15, the storm had moved into Canada and then dissipated over the ocean. One North Atlantic cargo ship, which had survived the Perfect Storm of 1991, floundered in 90 mph winds and 100-foot waves. All 33 crew members were lost.

More than 300 people died. In addition to those lost at sea or in tornadoes, some died during the cleanup. Pennsylvania had the highest death toll, primarily from overexertion-induced heart attacks and accidents caused by whiteout conditions.

Because meteorologists did not classify the event as a tropical storm, it was unnamed, earning monikers such as The No Name Storm, The Great Blizzard of ’93, The Storm of the Century, and the ’93 Superstorm.

For the first time in history, the National Weather Service used weather-prediction models and longer-range forecasts to provide advanced warning, enabling state governors to declare a state of emergency before snowstorms appeared. Doppler radar was not yet in widespread use, but forecasters in Florida were able to issue warnings with lead times of 30 minutes to 2 hours.

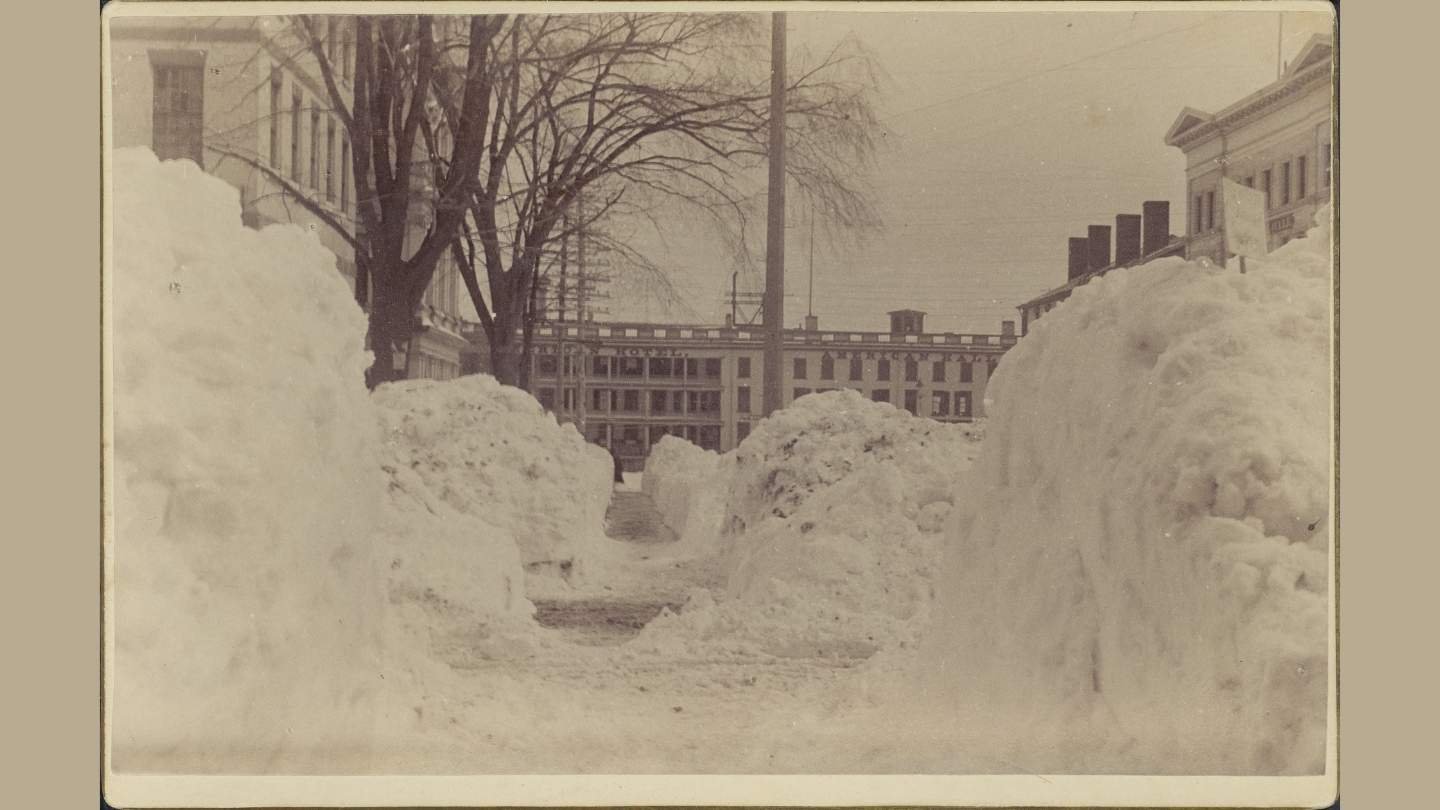

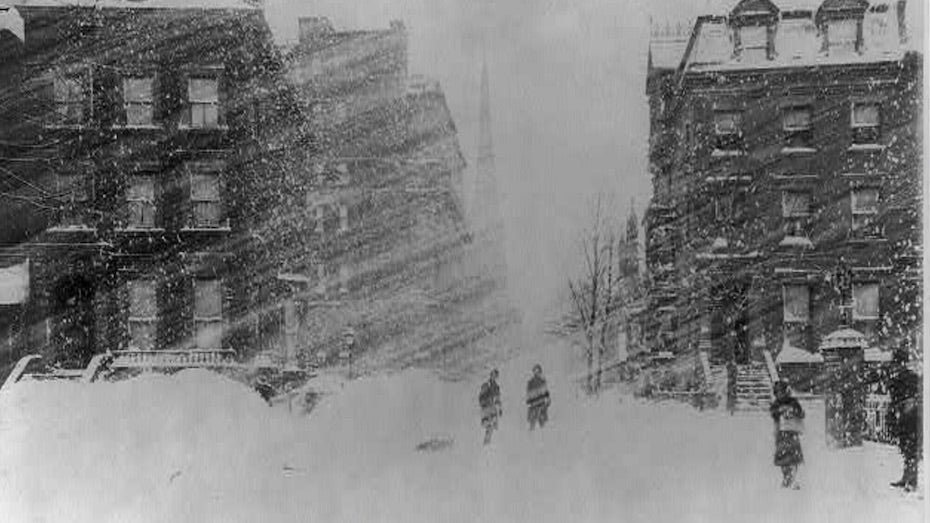

The Great White Hurricane

March 11 - 14, 1888

More than 100 years earlier, the Northeast experienced the Great White Hurricane. The days before the storm brought unusually warm temperatures in the 40s and 50s. Sunday, March 11, began with above-freezing temperatures and rainfall and ended with subzero temperatures as a cold Canadian front collided with warm air from the Gulf of Mexico.

On Monday, the rain turned into heavy snow, paralyzing transportation systems in major East Coast cities. Many workers were stranded. Fire stations were unable to respond, resulting in $25 million in damages (almost $1 billion today). Telegraph wires were damaged, leaving many cities isolated.

From March 11 through March 14, more than 60 inches of snow fell, accompanied by 45 mph winds. Snowdrifts buried three-story houses, and more than 400 deaths were reported.

The impassable road systems and the threat for future snowstorms prompted the cities of Boston and New York to develop underground subway systems, which were constructed within the next decade.

The Schoolhouse Blizzard

January 12, 1888— The day began with warm temperatures, a relief to Midwesterners who endured a brutal winter the year before, when temperatures plunged to 48 below. Even the 1887 summer was cut short by chilly weather in August, subzero temperatures by October, and excessive snowstorms in December. So when the thermometer climbed toward 50, people rejoiced. School children left home with high hopes, leaving winter coats behind.

The unexpected Arctic front covered 780 miles in only 17 hours and met a warm, wet front from the Gulf of Mexico, hitting Montana in the early morning and traveling through the Dakota Territory into Nebraska by the afternoon.

A South Dakota farmer said, “About 3:30, we heard a hideous roar. … At first we thought that it was the Omaha train which had been blocked and was trying to open the track. My wife and I were near the barn when the storm came as if it had slid out of sack. A hurricane-like wind blew, so that the snow drifted high in the air, and it became terribly cold. Within a few minutes, it was as dark as a cellar, and one could not see one’s hand in front of one’s face.” (Meier, 1930s)

A Norwegian farmer, Austin Rollag, wrote that “the air turned silent and ominous, and in the next moment, the blizzard crashed in.” Others reported ice needles flying at them in 60 mph winds, freezing their eyes shut. Some people died within a few steps of their door because of the whiteout conditions. Survivors lost limbs due to frostbite. One man’s frozen body remained discovered until April, when the snows melted.

Many schoolchildren were caught trying to get home without being dressed for cold weather. One family lost six children trying to get home from school. They were found with their arms wrapped around each other.

A 19-year-old Nebraska schoolteacher, Minnie Mae Freeman, led her 13 students through blinding snow and freezing winds to safety. The schoolhouse door blew away, and Freeman knew her students, dressed for warmer weather, would not survive in the fragile building. The teacher tied herself and her students together with rope, advised the children to huddle for warmth, and headed toward a farmhouse a mile away. After the students left the schoolhouse, the wind tore the roof off the building.

Estimates put the number of deaths, mostly people caught out in the weather, between 250 & 500. Many missing people were not reported in remote areas. The cold temperatures created ice skating in San Francisco, frozen water pipes in Los Angeles, and temperatures of 7 degrees below in Texas.

Other Memorable U.S. Snowstorms

The Knickerbocker Storm of 1922 was named because it collapsed the roof of the Washington, D.C. Knickerbocker Theater, killing or injuring over 200 people.

The Great Appalachian Storm of Thanksgiving weekend 1950 brought 62 inches of snow and caused 160 deaths.

The Chicago Blizzard of 1967 stranded 20,000 vehicles and over a thousand city buses. Helicopters delivered food and blankets to stranded motorists (I’m wondering if they dropped down a porta-potty!). A record number of babies were born at home that day. Some soon-to-be mothers were delivered to the hospitals by sled, bulldozer, or snowplow.

On March 29, 1970, Easter Sunday brought enough snow that our family’s car got stuck on our way home from church.

The Blizzard of 1996 caused many deaths, not only from heavy snowfall but also from the flooding that followed, which shut down all three NYC airports and turned the city into a ghost town.

Snowmaggedon in February 2010 hit Washington, D.C. Three major snowstorms in 20 days left 200,000 without power.

Snowzilla, aka Winter Storm Jonas, impacted 85 million people in 2016.

2019’s bomb cyclone (when a system’s pressure drops rapidly, causing the storm to intensify) affected 25 states, especially Colorado.

More Stories from American History

Sources on U.S. Snowstorms

Adventure-journal.com. “Minnie Mae Freeman Saved a Schoolroom Full of Children during One of the Country’s Deadliest Blizzards on Record – Adventure Journal,” August 11, 2023. https://www.adventure-journal.com/2023/08/minnie-mae-freeman-saved-a-schoolroom-full-of-children-during-one-of-the-countrys-deadliest-blizzards-on-record/?srsltid=AfmBOort2dw6c0I9crTlacrX5Ri_6ts77rzSvLtDhH-nsYgSZQwB9H-G.

Alferia. “The 1993 Storm of the Century - the Original Superstorm - a Retrospective and Analysis.” YouTube, March 21, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ClJtiIxtM84.

Armstrong, Tim. “On This Day: The 1993 Storm of the Century.” National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), March 9, 2017. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/1993-snow-storm-of-the-century.

———. “Superstorm of 1993 ‘Storm of the Century.’” Weather.gov, 2019. https://www.weather.gov/ilm/Superstorm93.

Brunner, Borgna. “The Great White Hurricane.” InfoPlease, February 28, 2017. https://www.infoplease.com/great-white-hurricane.

Bureau, US Census. “January 2025: The 1815 Battle of New Orleans.” Census.gov, 2026. https://www.census.gov/about/history/stories/monthly/2026/january-2026.html.

Burt, Christopher. “The Blizzard of 1888: America’s Greatest Snow Disaster.” www.wunderground.com, March 12, 2020. https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/the-blizzard-of-1888-americas-greatest-snow-disaster.

Ctdigitalarchive.org. “Verifying Connection,” 2026. https://collections.ctdigitalarchive.org/node/1185374.

Ford, Alyssa. “125 Years Ago, Deadly ‘Children’s Blizzard’ Blasted Minnesota | MinnPost.” MinnPost, January 11, 2013. https://www.minnpost.com/minnesota-history/2013/01/125-years-ago-deadly-children-s-blizzard-blasted-minnesota/.

Glenn, David. “30th Anniversary of the 1993 Superstorm.” WTVC, March 11, 2023. https://newschannel9.com/weather/stormtrack-9-blog/30th-anniversary-of-the-1993-superstorm.

Historic Ipswich . “The ‘Great White Hurricane,’ March 11, 1888,” December 14, 2025. https://historicipswich.net/2025/12/14/great-white-hurricane/.

Lakritz, Talia. “11 of the Biggest Blizzards to Ever Hit the US.” Business Insider, n.d. https://www.businessinsider.com/biggest-blizzards-us-winter-weather.

———. “Biggest Blizzards in History to Ever Hit the US.” Business Insider, January 5, 2024. https://www.businessinsider.com/biggest-blizzards-us-winter-weather#the-blizzard-of-1996-resulted-in-150-deaths-and-around-3-billion-in-damages-across-the-northeast-6.

Meier, O. W. “Recalling the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard of 1888, Ca. 1930s | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” www.gilderlehrman.org, n.d. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/recalling-schoolchildrens-blizzard-1888-ca-1930s.

Minnesota DNR. “With a Bang, Not a Whimper: The Winter of 1887-1888.” Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Accessed January 6, 2026. Files.dnr.state.mn.

Samuelson, Heidi. “The Blizzard of 1967.” Chicago History Museum, January 26, 2022. https://www.chicagohistory.org/1967blizzard/.

Staff, History.com. “The Biggest Snow Storms in US History | HISTORY.” HISTORY, March 14, 2017. https://www.history.com/articles/major-blizzards-in-u-s-history.

“Storm of the Century | Storm, Eastern Coast of North America [1993] | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/Storm-of-the-Century.

US Department of Commerce, NOAA. “March 12th-15th, 1993: Superstorm.” www.weather.gov, n.d. https://www.weather.gov/jan/superstorm_march_1993.

———. “The 1993 Storm of the Century.” www.weather.gov, n.d. https://www.weather.gov/tbw/93storm.

WGAL. “March 1993: ‘Storm of the Century’ Dumped Nearly Two Feet of Snow on South-Central Pa.” WGAL, March 13, 2023. https://www.wgal.com/article/south-central-pennsylvania-blizzard-of-1993-anniversary/43293741.

Wikipedia Contributors. “1993 Storm of the Century.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, April 3, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1993_Storm_of_the_Century.

Youtu.be, 2025. https://youtu.be/hC9Ux8fQWA4.