Sometimes, I enjoy a little complaining. Luckily, it only lasts until I open a book and travel back to another time. It lifts my grumbling heart to remember what life was like for the generations before me, the sacrifices and shortages they faced. I spend a lot of time reading about American life during World War II, and I am grateful to have missed that story-rich yet heartbreaking era when Americans gave so much.

Everything Changed

The greatest sacrifice was made by those who faced the true horrors of war on the battlefield. But folks on the homefront faced struggles, too.

Sixteen-year-old Iva Junk (now Iva Book - she is turning 100 this week) learned about the bombing of Pearl Harbor while listening to the radio. She and her family didn’t know what to think or expect. Marguerite Kerstetter, 91, recalls her dad being glued to the battery-powered radio during the war years. Jane Crone, the Snake Lady, had a more dramatic war announcement.

“My dad was getting ready to preach at his church in Refton, Pa. Someone was playing the organ, and a guy in a truck came flying in and ran right up to the pulpit, and said something to Dad. Dad said, ‘We all need to kneel and pray. The Japanese just bombed Pearl Harbor.’ I remember that because people screamed, some cried. Everyone got down on their knees.”

When I asked my grandfather, the late Jake Wert, what life was like during the war years, he said in his Pennsylvania Dutch, “We had nuttin’ before da war, and we had nuttin’ after, so we didn’t see much differnt.”

Most people remember those days differently.

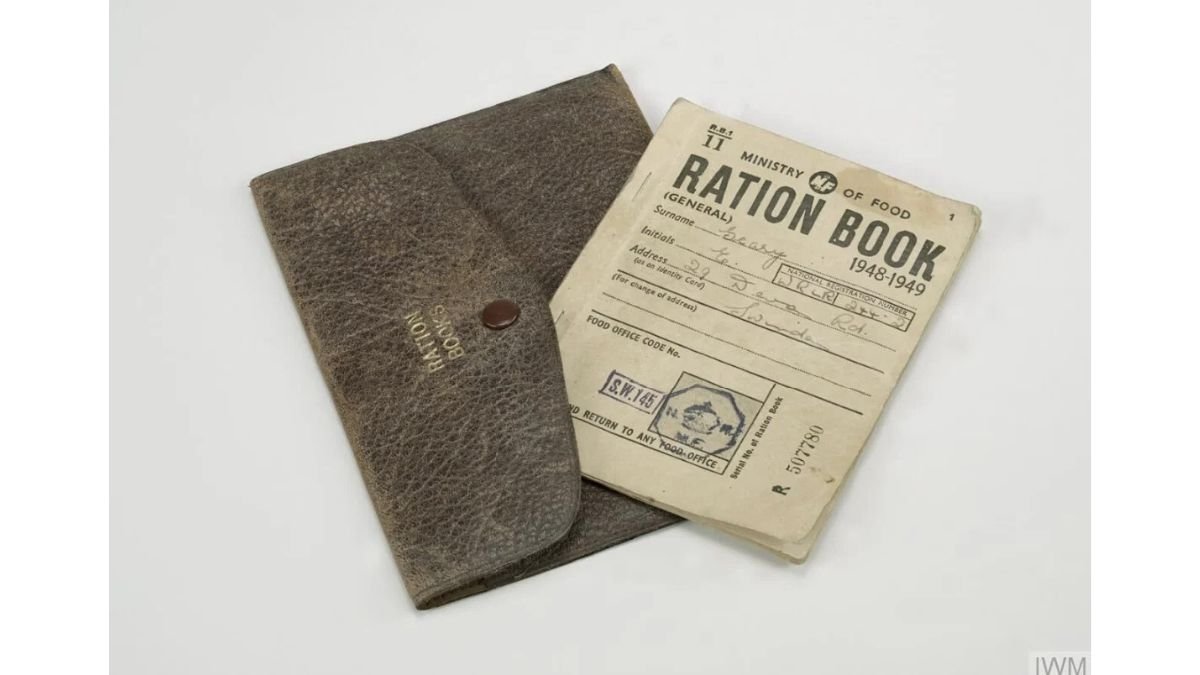

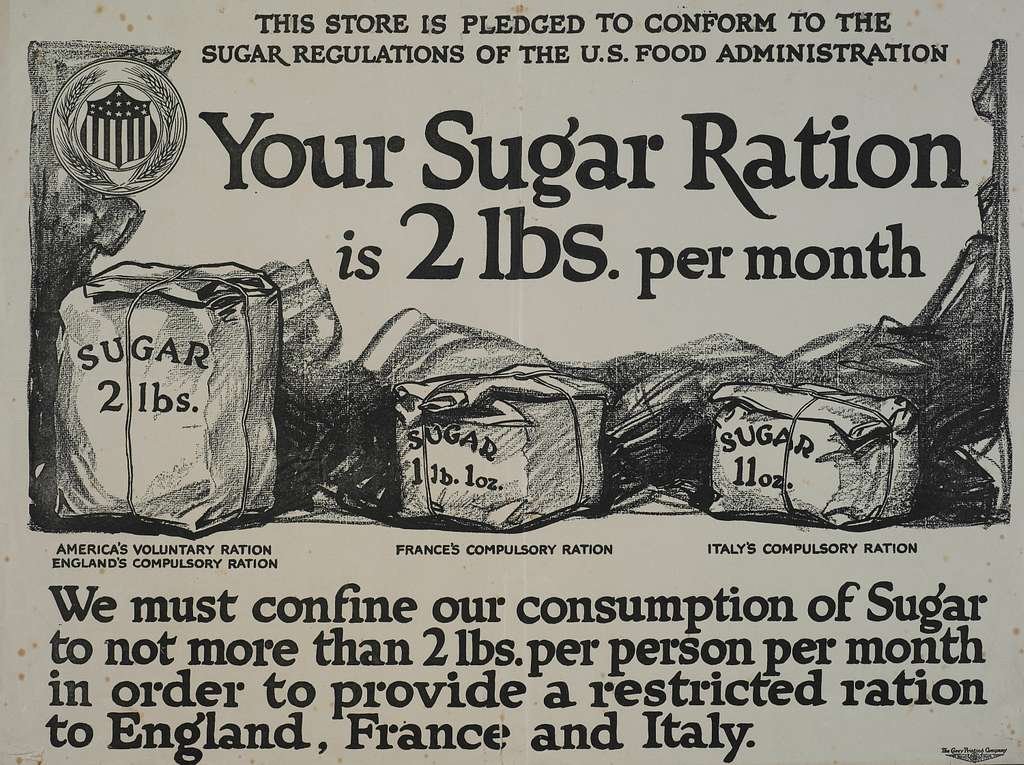

Food Rations

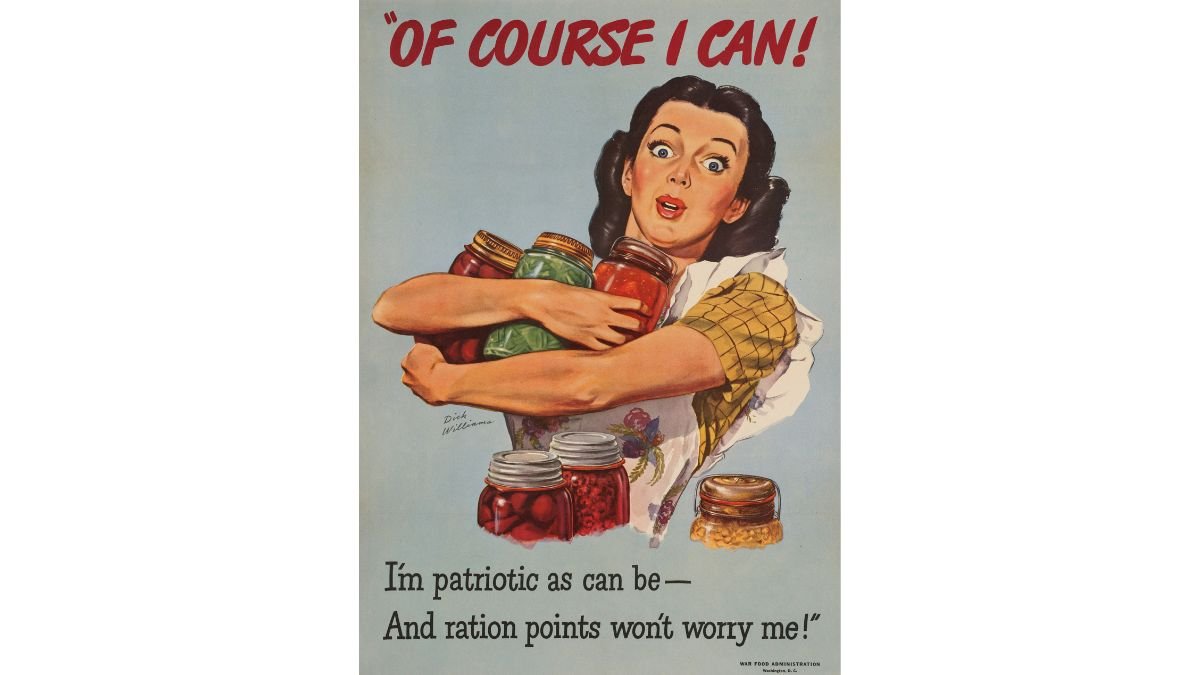

Life changed for many Americans when food and gasoline were rationed. Each person received a ration card, which allowed them to buy a specific amount of items. Being unable to buy unlimited sugar must have been difficult for Pennsylvanians who loved their baked goods.

Refton, PA resident Jane Crone explained the importance of ration cards. “On the day the war ended, I got in trouble with my mother. She had given me ration stamps to go to Dundoffs to buy some Lebanon bologna, bread, and a quart of milk. I came out of the store just as all the whistles sounded and people started running out of their houses.

"I ran home to see what was happening. We had a big black dog back then, and I threw everything on the chair and ran outside. When I went back in, the dog had torn up the bread and bologna. My mom was upset because those items required ration stamps, and now we wouldn’t have them,” she recalled.

The Department of Agriculture urged Americans to plant Victory Gardens to help feed their families and communities during times when local markets were limited. By 1943, over 20 million gardens provided about one-third of the food eaten by Americans. Victory gardens appeared not only on family farms and backyards but also in public parks, zoos, and vacant lots.

Many of these gardens were abandoned after the war. Aside from those who always relied on a garden, many people grew weary of the work involved. Land in urban areas was needed for the housing boom that followed the post-war baby boom.

Two large Victory Gardens still exist today. After the war, developers wanted to claim the Fenway Area for housing, but gardener Richard Parker led a campaign to save the garden. Today, Fenway Victory Garden covers more than seven acres with vegetables, herbs, flowers, and fruit trees. The Dowling Victory Garden in Minneapolis, Minnesota, also survived attempts to claim the land for development and now spans over three acres of garden plots.

Scrap Metal Drives

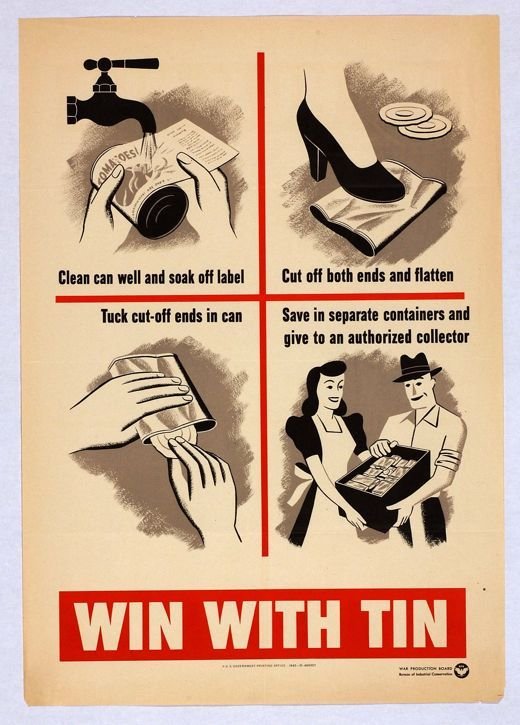

Food wasn’t the only commodity in short supply. War machines needed large amounts of copper, steel, and iron. Japan controlled the tin market, making tin scarce as well. Automobile factories shifted production to tanks, planes, and other military vehicles. Between 1942 and 1945, many consumers couldn’t buy new cars. Most families looked for used vehicles with low mileage. Because of the shortages of newly manufactured items, household appliance stores became repair shops.

Scrap metal drives were popular across the U.S. Tin can drives ignited competitions among towns, counties, and states. Some communities melted down Civil War cannons to aid the war effort. Others collected automobile fenders, kitchen pots and pans, used farm equipment, gardening tools, and wrought-iron fences from cemeteries.

The common elements in pennies and nickels changed in the early 1940s. The 1943 pennies were made of steel. A copper-silver, manganese alloy replaced the copper in nickels.

Silverware was no longer produced for civilians, and canned foods were rationed due to the tin shortage. People struggled to find items like razor blades, thumbtacks, paper clips, pins, needles, zippers, garden tools, and batteries. Children had to give up or donate their metal toys. Some efforts were made to limit the production of women’s makeup and alarm clocks, but these restrictions did not last the entire war.

No Burning Rubber

Ninety percent of the country’s rubber came from Southeast Asia. The U.S. government enforced reduced speed limits to conserve gasoline and reduce tire wear. A nationwide Victory Speed Limit of 35 mph banned joyriding and cruising, which could result in a driver losing their license. Tank production required one ton of rubber per vehicle; battleships needed seventy-five tons.

Rubber was also essential for gas masks, truck tires, and bomber planes. Some companies tried to produce synthetic rubber, but the process was costly and time-consuming. Americans had to sell back any extra tires and could keep only four tires plus one spare for their vehicles.

During the 1942 rubber drive, Americans donated their hot water bottles, rubber duckies, floor mats, galoshes, garden hoses, old tires, and raincoats. Some businesses paid a penny per pound. That year, 450,000 tons of low-quality rubber were collected.

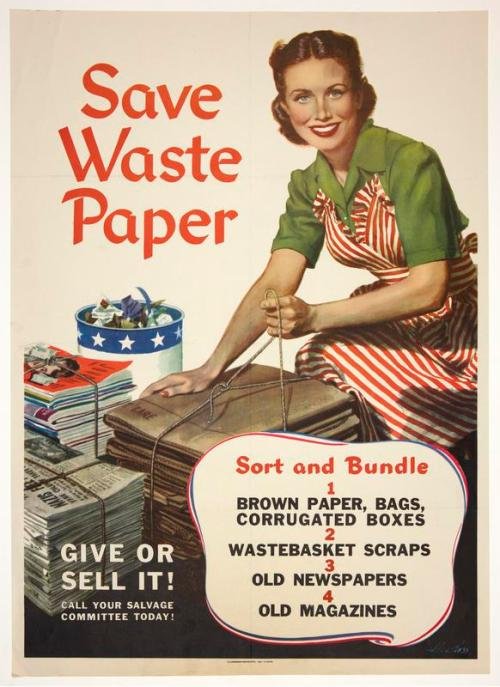

The lumber industry declined as workers left for higher-paying jobs or joined the military. The U.S. government loved paperwork, leading to shortages even of paper products. The military needed paper for letters, packaging, insulating barracks, and, of course, draft cards. School children signed up as Paper Troopers, collecting mounds of paper. Publishers faced a reduced paper supply, so they created paperback books, which are smaller with thinner pages and less white space.

A Use For Everything

Bacon fat and lard were collected to help produce explosives like nitroglycerine. Fats could be sold to local butchers for a few pennies per pound or extra ration points.

Once considered a weed that people pulled and threw away, milkweed was collected by children walking along the roads. Milkweed floss helped make life preservers that could keep a person afloat for forty hours.

Women’s stockings were used to make parachutes (lots of women’s stockings!) and gunpowder bags.

As I do a quick inventory of my pantry before the next grocery run, I feel deeply grateful for what I have. For my generation, rations and shortages are rare. (Let’s not talk about the 2020 toilet paper disaster. Some people I know are still stockpiling Charmin Ultra Soft.) Each week, I make my grocery list without worry, confident that whatever I need will be available on store shelves or online. I probably won’t go without, like those who lived before me.

More Stories From the World War 2 Era

Works Cited

American Gold Star Mothers, Inc. “American Gold Star Mothers, Inc.,” 2025. https://www.americangoldstarmothers.org/.

American Legion. “The American Legion a U.S. Veterans Association.” Legion.org, June 26, 2019. https://www.legion.org/.

Andrews, Evan. “5 Attacks on US Soil during World War II | HISTORY.” HISTORY, October 23, 2012. https://www.history.com/articles/5-attacks-on-u-s-soil-during-world-war-ii.

arlingtonhist. “From Barriers to Ballots Exhibit and 15-Minute History Series.” Arlington Historical Society, December 3, 2024. https://arlhist.org/aircraft-warning-service/.

Book, Iva. Interview, July 11, 2024.

Boston Public Library. “A Woman Holding a Jar of Jars with a Caption of Course I Can.” Unsplash.com. Unsplash, March 8, 2024. https://unsplash.com/photos/a-woman-holding-a-jar-of-jars-with-a-caption-of-course-i-can-1qJaR1b5JBE.

Cartwright, Mark. “Rationing in Wartime Britain.” World History Encyclopedia, June 21, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2491/rationing-in-wartime-britain/.

Crawford, Dick. Interview, October 20, 2025.

Crone, Jane. Interview, August 27, 2024.

Disabled American Veterans . “DAV.” DAV, 2019. https://www.dav.org/.

Editor, Peter Becker

Managing. “Local History: Civilian Aircraft Spotters Did Their Duty in WWII.” Tri-County Independent, April 18, 2016. https://www.tricountyindependent.com/story/opinion/columns/2016/04/18/local-history-civilian-aircraft-spotters/31439841007/.

Facebook.com. “Smithsonian - All Five Sullivan Brothers Died When Japanese...,” 2016. https://www.facebook.com/Smithsonian/posts/all-five-sullivan-brothers-died-when-japanese-torpedoes-sank-the-uss-juneau-in-1/1098775052283629/.

Families, America’s Gold Star. “America’s Gold Star Families | Home.” America’s Gold Star Families, n.d. https://americasgoldstarfamilies.org/.

———. “America’s Gold Star Families | Programs & Services.” America’s Gold Star Families, n.d. https://americasgoldstarfamilies.org/what-we-do/programs-and-services.

fenwayvictorygardens.org. “The Richard D. Parker Memorial Victory Gardens,” n.d. https://fenwayvictorygardens.org/.

For, HOPE. “An Honor No One Wants: What Is a Gold Star Family and How Is It Different from a Blue Star Family?” Hope for the Warriors, September 23, 2017. https://www.hopeforthewarriors.org/an-honor-no-one-wants-what-is-a-gold-star-family-and-how-is-it-different-from-a-blue-star-family/.

Helwig, Brady. “The U.S. Synthetic Rubber Program: An Industrial Policy Triumph during World War II - American Affairs Journal.” American Affairs Journal, February 20, 2025. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2025/02/the-u-s-synthetic-rubber-program-an-industrial-policy-triumph-during-world-war-ii/.

History.com Editors. “Draft Age Is Lowered to 18 | November 11, 1942 | HISTORY.” HISTORY, November 5, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/november-11/draft-age-is-lowered-to-18.

Kerstetter, Marguerite. Interview, February 27, 2025.

Legacies Alive. “Resources for Gold Star Families - Legacies Alive (Support & Services),” August 19, 2020. https://legaciesalive.com/gold-star-families/resources/.

Loc.gov. “Service on the Home Front,” 2016. https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b49007/.

Loc.gov. “Victory Gardens,” 2017. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017696713/resource/.

Lost, America. “Home - Blue Star Families.” Blue Star Families, 2018. https://bluestarfam.org/.

Milton, John. “Sonnet 19: When I Consider How My Light Is Spent… | Poetry Foundation.” Poetry Foundation, 2019. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44750/sonnet-19-when-i-consider-how-my-light-is-spent.

National Military Family Association. “National Military Family Association.” National Military Family Association, 2019. https://www.militaryfamily.org/.

Ohio.gov. “Robert L. Queisser,” 2020. https://dvs.ohio.gov/hall-of-fame/honorees/hof-honorees-2010s/Robert-L-Queisser.

Sarah, Sundin. “Make It Do - Metal Shortages in World War II,” March 30, 2022. https://www.sarahsundin.com/make-it-do-metal-shortages-in-world-war-ii/.

Save Waste Paper Poster, 1944. n.d. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum: MO 2005.13.35.104.

Springate, Megan. “Material Drives on the World War II Home Front (U.S. National Park Service).” www.nps.gov, May 16, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/material-drives-on-the-world-war-ii-home-front.htm.

———. “The American Home Front during World War II: Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens (U.S. National Park Service).” www.nps.gov, n.d. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/homefront-ration-recycle-garden.htm.

———. “Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front (U.S. National Park Service).” www.nps.gov, November 16, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/victory-gardens-on-the-world-war-ii-home-front.htm.

Springate, Megan . “Introduction to Life on the World War II Home Front in the Greater United States (U.S. National Park Service).” www.nps.gov, November 16, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/introduction-to-life-on-the-home-front-in-the-greater-united-states.htm.

The. “Photo by the Oregon State University Collections and Archives on Unsplash.” Unsplash.com. Unsplash, September 28, 2024. https://unsplash.com/photos/PLaJLD9RTqk.

The National WWII Museum. “Research Starters: The Draft and World War II.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, n.d. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/draft-and-wwii.

The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. “WWII Veteran Statistics | the National WWII Museum | New Orleans,” 2019. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/wwii-veteran-statistics.

USO. “United Service Organizations.” United Service Organizations, 2019. https://www.uso.org/.

Varner, Philip. Interview, May 13, 2025.

visitww2.org. “Civilian Defense & Air Raid Wardens - World War II American Experience,” November 23, 2021. https://visitww2.org/office-of-civilian-defense-air-raid-wardens/.

Whiting, Karen H, and Jocelyn Green. Stories of Faith and Courage from the Home Front. Battlefields & Blessings, 2012.

Wounded Warrior Project. “WWP | Veterans Charity Organization: Nonprofit Help for Wounded Military.” Woundedwarriorproject.org, 2019. https://www.woundedwarriorproject.org/.